By Denise Jacques

My favourite television program is Finding Your Roots. I am moved by how often the male and female guests are reduced to tears on discovering some aspect of family history. VHS had a parallel experience when we were contacted by a local family with a cache of Great War letters. We were asked for advice on preserving the letters and making them accessible.

Fellow director Tom Carter proposed that UBC iSchool digitize the material and create a basic timeline. This is happening to the satisfaction of the family involved. Through the wonders of the electronic world, we have tried to trace the unfolding story of two brothers, Peter and Jack Dueck who fought for Canada during the Great War. While we drew on personal information from attestation files and census records, we also examined the interplay between the two brothers’ individual stories and Canadian war-time policy.

To pick up the story, in 1916 Prime Minister Robert Borden in his New Year’s message pledged to create an army of 500,000 Canadian soldiers out of a population of eight million. Meanwhile in Edmonton, Colonel Peter Edwin Bowen attempted to raise a new regiment – the 202nd or the “Sportsman Battalion” as a unit of the Canadian Expeditionary Army. The sporting title was designed to offset flagging enlistment among the middle class, who were increasingly intimidated by growing causality lists. The unit began recruiting in Alberta on 4 February 1916, and Peter Dueck, a young Mennonite born in Manitoba, joined on 8 April, Bowen himself signed his papers. The location was “Camrose.”

Already, this is a story. The Mennonites were firmly passivists: the family spoke Low Deutsch. Mother had been born in Mariupol. Why would Peter Dueck – followed by his brother Jack in 1918 – join up for a fight in the mud of France? We still seek the answer to that question.

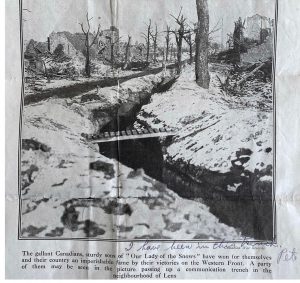

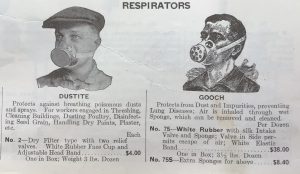

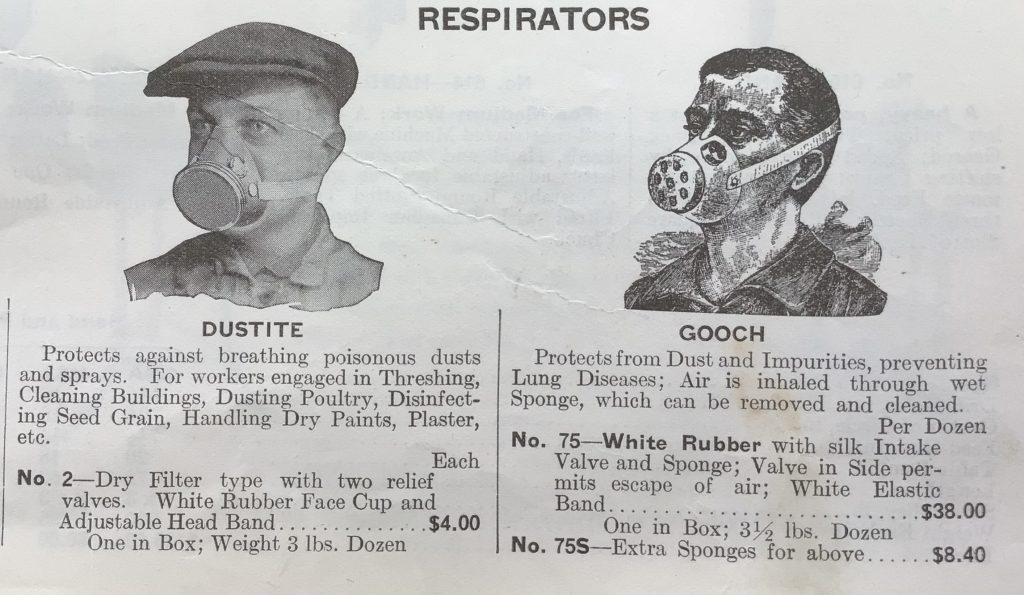

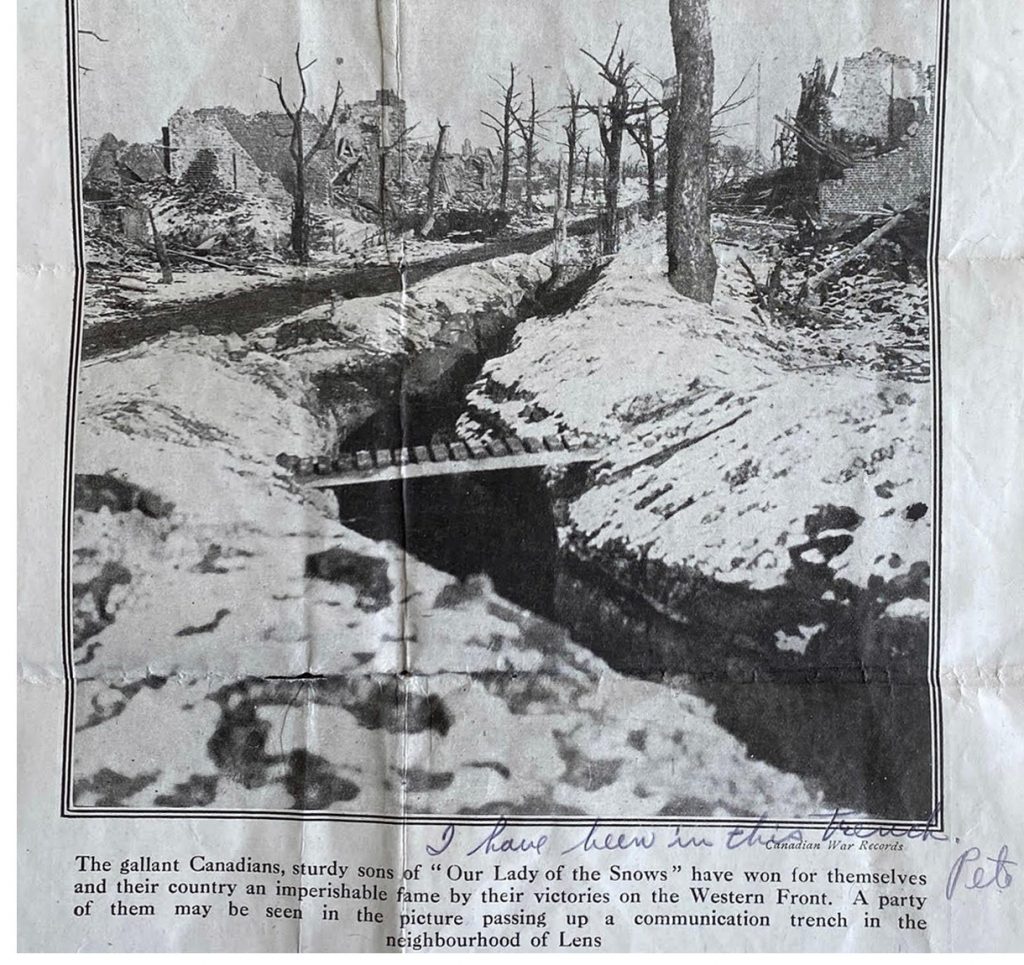

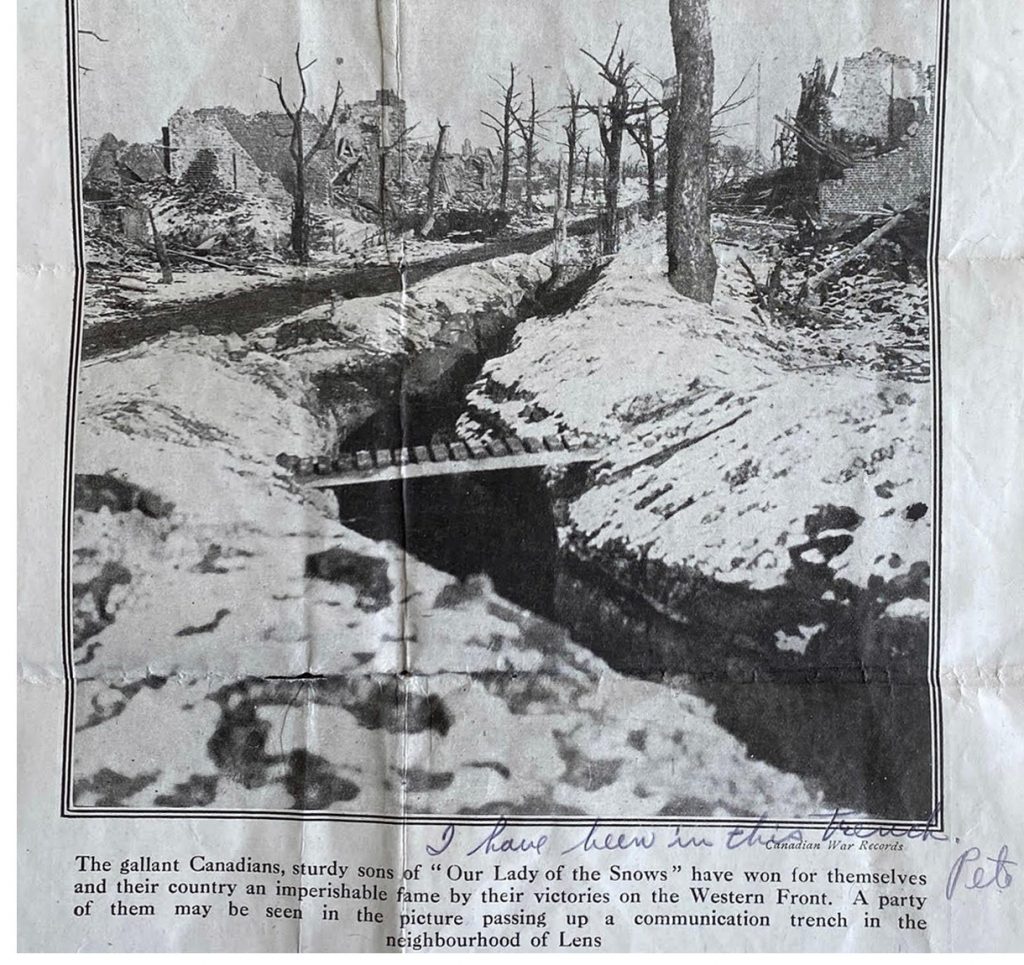

Our prime clue in unravelling what happened next is contained in Peter’s extensive medical records. They are helpful in deciphering the history of the war and the realities of the trenches. We know from his medical files that Peter would suffer from several complaints. Other than shrapnel from an exploding shell lodged near the femur – that may not have entirely been identified until March 1919 – Peter was diagnosed with ‘disordered action of the heart’ (DAH), ‘nervous debility’ or ‘valvular disease of the heart’ (VDH). Separating heart disease from shell shock induced by shell fire or in intense combat was hard. Records reveal that Peter died in Point Grey, Vancouver, from war wounds in April 1921, though it is unclear what finally killed him. Peter’s later regiment, the 50th Battalion, received battle honours for the Somme, Vimy, Passchendaele, and Amiens (among others); some of these names are listed in Dueck’s records. Whether the shrapnel or heart disease ultimately caused death, Peter had been through hell.

Meanwhile Jack Dueck the older brother had a much better war. Jack joined as a sapper, building roads and clearing mines. He entered the war in 1918 and judging from the lack of wounds he did not experience the same frontline action.

When the war finally ended both brothers availed themselves of public policy initiatives. In Canada’s 1917 Soldier Settlement Act and its 1919 revision made land grants and loans available to soldiers. A person in active service during the First World War was eligible for a free homestead under the Act. This legislation allowed the overseeing Board to buy Crown lands, settle returned soldiers and create valuable farmland. Recipients of property were expected to work it for a term before they could buy it outright; the Settlement Board also provided loans for equipment, livestock, and buildings By 1924, over 30,000 former soldiers had been settled on former Crown lands in the prairie provinces. However, the initiative was not entirely successful; most of the land had never been farmed and required years of work to make it profitable. Additionally, many settlers had never planted and found the work and isolation difficult.

Peter and Jack applied for land near the Peace River in October 1919. As they do not appear in later census material their homesteading efforts were likely unsuccessful. Peter‘s diminishing health may have been the cause. We are still hopeful that more information can be researched. However, the interplay between public policy and private lives provides a compelling narrative of individuals caught in the interplay of history. We have just begun unraveling the story.