Summaries of Talks and Field Trips - 2014

Glimpses of the Past through description, related books and internet connections

The Founding Role of French Canadians in British Columbia

Absent from common historical memory is the fact that French Canadians were at the forefront when the Rockies were crossed for furs and prospects at the end of the 18th century. For the next half century French Canadians were the largest group of non-indigenous people in the future province and French was the principal non-indigenous language. It was the French Canadians who: facilitated the first non-indigenous overland crossings of British Columbia by Alexander Mackenzie and Simon Fraser; sustained the subsequent fur economy at the various fur trade posts in the Pacific Northwest and initiated non-wholly indigenous settlement with indigenous women as is evidenced today by the large number of French Canadian names found in First Nations communities. Very importantly, it was the French Canadians’ hard work that ensured, when the Pacific Northwest was divided in 1846, the United States would not get it all as it dearly sought, but the northern half would go to Britain, giving today’s Canada its Pacific shoreline and bringing the province of British Columbia into being. [see Jean Barman’s French Canadians, Furs, and Indigenous women: The Pacific Northwest Reconsidered, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014]

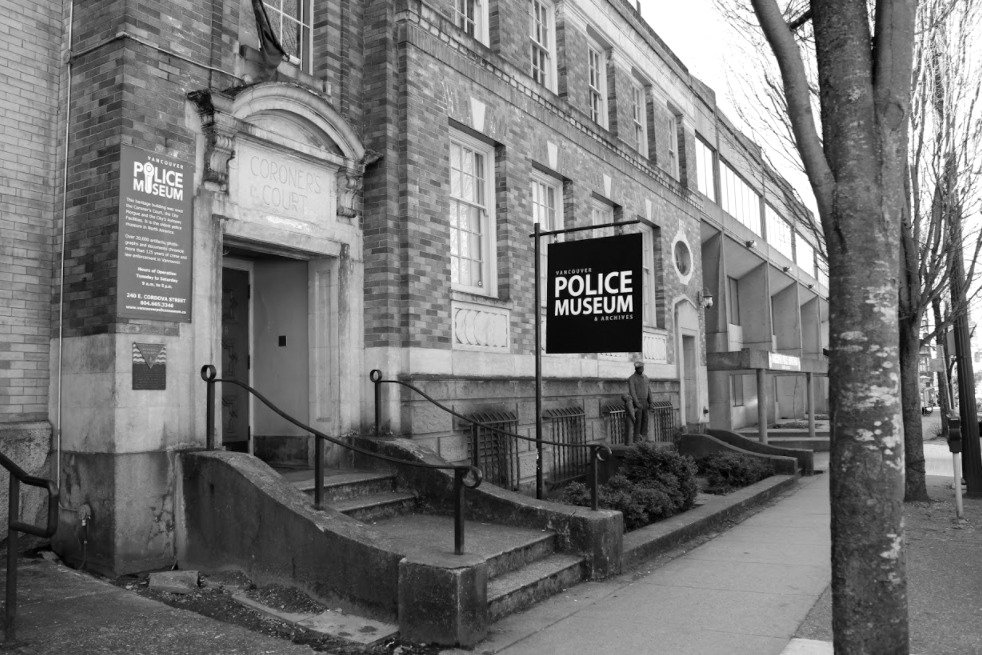

Vancouver Police Museum, Morgue and Important Cases

Built at 240 East Cordova Street by the City of Vancouver in 1932, the building that housed from that day the combined facilities of the Coroner’s Court, City Morgue, autopsy facilities and City crime laboratory, was a vibrant place from that date until the 1980s when the services were defused throughout the growing city. Now, functioning as the Vancouver Police Museum, it is considered one of finest museums of its kind in North America. It houses over 20,000 documents (from history of squads to annual reports), photographs and artifacts (from badges to confiscated items) dating from the mid-1800s, all of which come to life in interactive displays. Aside from regular visits by curious Vancouverites and tourists, twelve thousand visiting elementary and high school students each year learn the hands-on secrets of forensic science to solve crimes. Special displays, for example, focus on the still unsolved 1947 Babes in the Woods Murders, the 1959 autopsy of movie legend Errol Flynn, and the 1965 Milkshake Murder that sent a CKNW public relations man to prison for life. The Vancouver Police Museum is one of the historical gems of Vancouver.

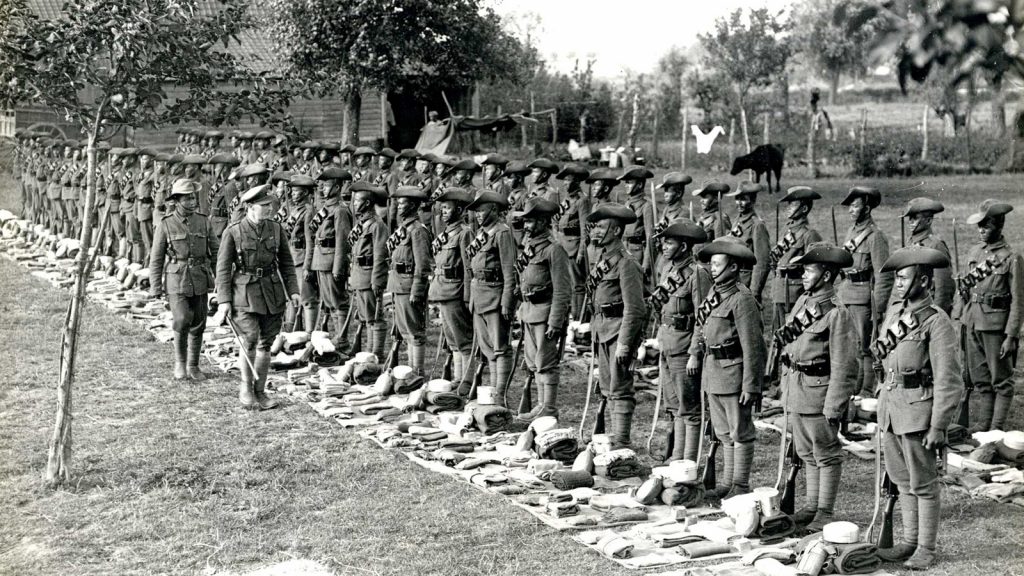

The Other Western Front – British Columbia and the Great War

British Columbia’s proportional participation in the 1914-18 Great War was considerable, the province even having but only for a brief time, two submarines in its tiny Pacific Coast fleet. Canada in all contributed 620,000 soldiers, over 60,000 of whom never returned. On the home front from during the war years, women got the vote, large numbers of people left the farms to work in munitions factories, the French and English Canadian split widened, prohibition denied the population access to alcohol and a “temporary” income tax came into effect. An impressive memorial to Canada’s war effort stands on a ridge at Vimy, Pas-de-Calais, France. Here in 1917 the four divisions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force captured the ridge from the Germans. It has become a nationalist focus for the country because of the then use of technical and tactical innovation, meticulous planning, powerful artillery support and extensive training. [see Greg Dickson and Mark Forsythe’s From the West Coast to the Western Front: British Columbians and the Great War. Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2014]

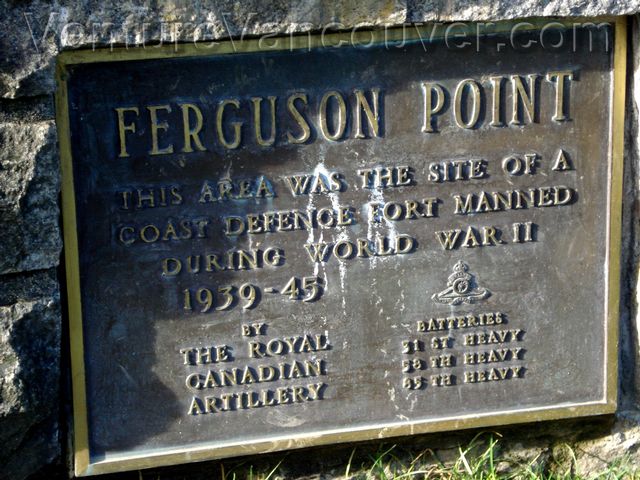

Stanley Park Fort on Ferguson Point

Most people know the peninsula only as a public park, but Stanley Park has a military history. In 1914 the point of land near Siwash Rock was occupied by a temporary gun battery when an attack by Germany’s East Asia naval squadron was considered likely. In the Second World War the Japanese navy was regarded as the greatest threat, and as a result a two battery gun emplacement was built at Ferguson Point, in front of what is now the Teahouse in Stanley Park. Two large guns were placed forty meters from the cliff’s edge as part of a large concrete structure that included an underground magazine for ammunition and three large searchlights. A camp for 140 men was built nearby at Third Beach. Vancouver’s Town Planning Commission had opposed the Ferguson Point battery at the outset, and when the war was over the guns were quickly removed and the concrete installations covered over. Stanley Park’s wartime history, like the gun emplacements that stood guard over Burrard Inlet at Ferguson Point from 1939 to 1945, has been buried and mostly forgotten. [See Peter Moogk, Vancouver Defended: A History of the Men and Guns of the Lower Mainland Defences, 1859-1949 (Surrey, BC: 1978)].

The Third CPR Station: 100 years old

The first CPR station lasted almost thirteen years as it was nothing more than a large wooden shed on the CPR docks on the shoreline below the escarpment, the bluff which was becoming dotted with CPR executive mansions. This first terminus was replaced in the late 1890s by a chateau gothic revival second station with its entrance off Granville Street. However, a quickly growing city rendered the charming structure too small and so, in 1914, it was replaced nearby along Cordova Street by a Montreal designed station. Still seen today, this large neo-classical colonnaded structure opened coincidently on August 1, the day Germany declared war on Russia; understandably there was no mention of the event in the newspapers. It was under threat of demolition until 1970 when the disastrously conceived “Project 200” failed. Still not a done-deal, its existence was finally assured in 1977 when the station became an integral part of the Seabus terminal. Since then the lobby has regained its original elegance with the stripping back to its original levels and with the refurbishment of the 1916 Adelaide Langford paintings showing scenes from the train trip between Vancouver and Calgary. A treasure saved.

The Art of the Impossible: Dave Barrett and the NDP in Power, 1972-1975

The Dave Barrett-led New Democratic Party’s term in power from 1972-1975 passed a remarkable amount of progressive legislation, much of which remains firmly in place today. Some of the changes brought about were the formation of the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia (ICBC), creation of the Agricultural Land Reserve, expanded provincial parkland, the BC Ambulance Service, free prescription drugs for seniors and even the banning of pay toilets. The dizzying speed of change brought about a reaction and his party’s defeat in 1975. [see Geoff Meggs and Rod Mickleburgh, The Art of the Impossible: Dave Barrett and the NDP in Power, 1972-1975, Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2012]

Vancouver’s East End Roots: Strathcona North of Hastings

A walk around the now quiet area of Vancouver’s East side, which includes the historic Japanese centre of the city, reveals little known facts about Vancouver. For example, wooden blocks provided the original foundation for Vancouver streets. Alexander Street, now a quiet mix of low rise office buildings and houses, used to be a thriving brothel district. Al that remains are the well-built row houses built in the style of the time. Many more secrets lay hidden in this early part of Vancouver.

The Life of a Building: The Continental Hotel

The Continental Hotel is an otherwise nondescript building at the north end of the Granville Street bridge. A closer examination, however, reveals the fascinating lives of two respected clothiers who in 1911 went into building development close the end of a boom cycle and lost the building when the economy went bust. Both bon vivants, one thrived while the other sank into poverty. The hotel went through several iterations, was purchased by the city, surrounded by off-ramps of the 1950s bridge, having ended its usefulness, will soon be torn down.

Moving Images of Parades and Royal Visits from 1936

Colourful moving images of events such as parades with their creative floats and royal visits with excited crowds capture the past enthusiasm of Vancouverites for not only celebrations but visiting royalty. They give us a yardstick of how much we have changed and, at the same time, how much remains the same. Captured forever by the movie camera is the excitement of children and their endless rehearsals preparing for the visit of a queen and the more subtle expressions of a tired monarch just wanting to get on with it after a long, touring day.

Image of Vancouver Through Time

With a little bit of detective work, one can reveal, through artistic murals, postcards, advertisements in newspapers or on posters, etc., just how Vancouver artists depicted the city and province. Although this type of art is eschewed by art galleries, reclaiming it is nonetheless important for it helps to sustain the veracity of our historical narrative. Fortunately, through the internet these disparate and once-thought-lost gems have begun to emerge helping us to see our past more clearly.

The Rise and Fall of the Pacific Hockey Association, 1911-1926

Wet and mild Vancouver did not have proper space for a professionally organized hockey team until the Patrick brothers came along in 1911 and built the 10,500 seat Denman Arena replete with artificial ice. This new arena at the corner of Denman and Georgia Streets became the home base for Vancouver’s contribution to the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, the Vancouver Millionaires.

By 1915 the Millionaires were a powerhouse in ice hockey and went on to win the Stanley Cup that year against the Ottawa Senators. The Association lasted until 1926 and the Arena burned down in 1936. [see Craig H. Bowlsby’s Empire of Ice: The Rise and Fall of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, 1911-1926, Vancouver: A Knights of Winter Publications, 2012]

Suspect Properties: The Vancouver Origins of the Liquidation of Japanese Canadian property

Wet and mild Vancouver did not have proper space for a professionally organized hockey team until the Patrick brothers came along in 1911 and built the 10,500 seat Denman Arena replete with artificial ice. This new arena at the corner of Denman and Georgia Streets became the home base for Vancouver’s contribution to the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, the Vancouver Millionaires.

By 1915 the Millionaires were a powerhouse in ice hockey and went on to win the Stanley Cup that year against the Ottawa Senators. The Association lasted until 1926 and the Arena burned down in 1936. [see Craig H. Bowlsby’s Empire of Ice: The Rise and Fall of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, 1911-1926, Vancouver: A Knights of Winter Publications, 2012]